Acas Carotid Trial

While the NASCET trial showed the benefit of CEA for patients symptomatic from carotid artery stenosis, the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) trial sought to test whether a morbidity and mortality benefit existed for treated asymptomatic patients with CEA. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stent Trial (CREST) was designed in the late 1990s and was started in 2000. 1,2 At the time, there had been no adequate, randomized comparisons of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and protected carotid artery stenting (CAS). These include the ACAS, VA asymptomatic trial, the MAYO carotid trial, and the CASANOVA trial. The VA asymptomatic trial showed benefit of CEA in transient ischemic attack was included. The Mayo trial was halted prematurely due to the high rate of complication in the surgical arm. In the ACAS study, carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic moderate to severe carotid stenosis (60%-99% luminal obstruction) reduced the absolute risk of ipsilateral stroke or death at five years.

Abstract

Several large randomized clinical trials in North America and Europe concluded over a decade ago that carotid endarterectomy plus medical management was significantly better than medical management alone for stroke prevention in either symptomatic or asymptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis. Percutaneous carotid angioplasty now represents another treatment option that currently seems most appropriate either in the context of prospectively randomized trials or for patients who are at a higher than average risk for conventional surgical treatment.

Introduction and context

Few modern clinical problems have provoked as much controversy as extracranial carotid artery disease. Prompted by concern that carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was being performed for uncertain indications during the 1980s, four randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were sponsored by the National Institutes of Health in the United States and by the Medical Research Council in the United Kingdom in order to determine the benefit of CEA in symptomatic patients and for asymptomatic carotid stenosis [-]. These included the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET), the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST), the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) and the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST), all of which remain the foundation for proper patient selection and should be thoroughly familiar to clinicians who recommend or perform any kind of carotid intervention.

Table 1 contains data from these four important investigations. It must be noted that the methods for estimating the percentage of carotid stenosis differed in the North American (NASCET, ACAS) and the European (ECST, ACST) trials; the former used the diameter of the uninvolved internal carotid artery distal to the index lesion as the denominator, whereas the latter employed the projected normal diameter of the internal carotid bulb. Nevertheless, the conclusions reached by these trials were reasonably consistent and can be summarized as follows.

Table 1.

| RCT | Severity of stenosis (%) | 30-day surgical CSM (%) | Reported follow-up period (years) | Long-term event rate | Relative risk reduction (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid endarterectomy (%) | Medical management (%) | ||||||

| Symptomatic patients | |||||||

| NASCET [1] | 70-99 | 5.8 | 2 | 9.0a | 26.0a | 65 | <0.001 |

| NASCET [2] | 50-69 | 6.7 | 5 | 15.7a | 22.2a | 29 | 0.045 |

| ECST [3] | 70-99 | 7.5 | 3 | 12.3b | 21.9b | 45 | <0.01 |

| ECST [4,5] | 50-69 | 7.9 | 8 | 18.4b | 15.6b | None | - |

| Asymptomatic patients | |||||||

| ACAS [6] | 60-99 | 2.3 | 5 | 5.1a | 11.0a | 53 | 0.004 |

| ACST [7] | 60-99 | 3.1 | 5 | 6.4c | 11.8c | 46 | <0.0001 |

Acas Carotid Trial Training

aIncludes 30-day strokes and deaths but only ipsilateral late strokes. bIncludes 30-day strokes and deaths and all late strokes. cIncludes 30-day strokes (but not deaths) and all late strokes. ACAS, Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study; ACST, Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial; CSM, combined stroke and/or mortality rate; ECST, European Carotid Surgery Trial; NASCET, North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

First, the 30-day combined stroke or mortality rates for CEA were two to three times higher in symptomatic patients than in patients who had asymptomatic carotid stenosis. This may reflect the potential of symptomatic lesions to cause intraoperative cerebral emboli during carotid manipulation.

Second, the benefit of CEA was greater and became obvious within shorter periods of follow-up in patients who had previous symptoms in conjunction with severe carotid stenosis measuring at least 70% of lumen diameter. The relative risk reduction associated with CEA for 50-69% stenosis was only marginally significant (P = 0.045) in the NASCET, and the ECST showed no risk reduction at all for CEA in this particular group of patients.

Third, in comparison to symptomatic patients in the NASCET and ECST, patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis in the ACAS and the ACST had lower long-term event rates irrespective of whether they were randomized to CEA or medical management. Furthermore, while CEA provided a significant overall reduction of relative risk in the ACAS, this benefit seemed substantially less impressive in women (17 versus 66% in men, P = 0.10), probably because they tended to have a higher incidence of perioperative stroke or death (3.6 versus 1.7%, P = 0.12).

Fourth, the ACST did not substantiate the apparent lesser benefit of CEA that was found in asymptomatic women by the ACAS, but this might be explained by the fact that the ACST excluded the risk for perioperative stroke or death (3.6% in women, 2.5% in men) from its subset analyses. The ACST also reported that unoperated patients with 60-79% stenosis were as likely as those with 80-99% stenosis to have future strokes. The ACAS did not further stratify its criterion of 60-99% stenosis, but other non-randomized case series strongly suggest that asymptomatic 60-79% stenosis has a very low risk for stroke and can be kept under surveillance by duplex scanning [].

Fifth, the ‘number needed to treat’ (NNT) is defined as the number of patients who would have to undergo CEA in order to prevent one long-term adverse event. In the NASCET, this ranged from an NNT of six for patients who had 70-99% stenosis, to an NNT of 15 for patients with 50-69% stenosis [,]. The corresponding NNT was 19 for all patients in the ACAS, and it undoubtedly was even higher in women [].

Recent advances

Percutaneous carotid angioplasty (PCA) was described in isolated case reports during the late 1970s and has since been the topic of more than 20 large case series, over a dozen industry-sponsored registries, and a few independent trials []. Many of these studies became obsolete almost immediately because of additional refinements in endovascular technology, such as carotid stents and over-the-wire cerebral embolic protection devices []. Table 2 summarizes the results from four RCTs that were published in peer reviewed journals [-] and frequently have been cited on the basis of their timeliness or their controversial aspects, depending on the perspective from which they are viewed [16].

Table 2.

| RCT | Clinical features | Angioplasty adjuncts | 30-day surgical or procedural CSM | Long-term event rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms (%) | Stenosis (%) | Stent (%) | CEP (%) | CEA (%) | PCA (%) | P-value | CEA (%) | CA (%) | P-value | |

| CAVATAS [11] | 97 | Mean: 85±10 | 26 | None | 9.9 | 10 | NS | 14.2a | 14.3a | NS |

| SAPPHIREb [12,13] | 29 | ≥50 (symptomatic) | 100 | 100 | 9.8c | 4.8c | 0.09 | 26.9d | 24.6d | 0.71 |

| ≥80 (asymptomatic) | ||||||||||

| SPACE [14] | 100 | ≥50 (NASCET) | 100 | 27 | 6.3e | 6.8e | 0.09 | NR | NR | - |

| ≥70 (ECST) | ||||||||||

| EVA-3S [15] | 100 | ≥60 | 100 | 92 | 3.9f | 9.6f | 0.01 | 4.2g | 10.2g | 0.008 |

aDeath or disabling stroke within 3 years. bIndustry sponsored (Cordis Corporation). cDeath, stroke or myocardial infarction. dDeath, stroke or myocardial infarction within 30 days or death or ipsilateral stroke within 3 years. eDeath or ipsilateral ischemic stroke. fAny death or stroke. gAny death or stroke within 30 days plus ipsilateral stroke between 31 days and 6 months. CAVATAS, Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CEP, cerebral embolic protection; CSM, combined stroke and/or mortality rate; EVA-3S, Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis trial; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; PCA, percutaneous carotid angioplasty; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAPPHIRE, Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy trial; SPACE, Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy trial.

CAVATAS

Conducted from 1992 to 1997, the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS) was the earliest trial of PCA versus CEA to be independently funded and to capture international attention. Each of the participating centers had to designate one or more radiologists with prior training in angioplasty techniques, but there was no requirement for previous experience with the carotid artery. The CAVATAS showed no long-term outcome differences between PCA and CEA in symptomatic patients, but its credibility was eroded by a 30-day stroke or mortality rate for CEA (9.9%) that was much worse than generally had been reported. Moreover, carotid stents were used in only 26% of the patients who received PCA, a factor that could have contributed to a high incidence of recurrent ≥70% stenosis (18 versus 5.2% for CEA, P = 0.0001) at just 1 year of follow-up []. Cerebral embolic protection devices were unavailable at that time, so this adjunct was not used in the CAVATAS.

SAPPHIRE

The Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) trial was funded by industry and for this reason may not have quite the cache of an independent RCT. It enrolled asymptomatic patients with ≥80% stenosis in addition to symptomatic patients with ≥50% stenosis, and it employed a unique primary end point of stroke, death and/or myocardial infarction (MI). This represented a departure from the traditional composite end point of stroke and/or death, especially since it included asymptomatic elevations in cardiac isoenzyme and troponin levels that had not been measured in most previous studies of CEA. The SAPPHIRE trial did have a number of practical features, however. First, it only accepted patients who were less than ideal surgical candidates because of serious cardiac disease (e.g. recent MI or unstable angina, congestive heart failure, <30% ejection fraction) or treacherous local anatomy, such as high carotid lesions near the skull base, prior cervical irradiation, or recurrent stenosis after prior CEA. Second, its interventionalists were strictly vetted and had a median past experience with 64 PCAs. Third, every PCA procedure in the trial was done using a cerebral embolic protection device and a carotid stent, both of which were manufactured by the sponsor (Cordis Corporation).

Much of the difference in 30-day end points could be attributed to a higher incidence of ‘chemical’ MIs after CEA, but the ultimate conclusion of the trial was that PCA provided an equivalent alternative in patients who were perceived to be at high risk for CEA. The SAPPHIRE trial has been criticized on the grounds that the majority (70%) of its patients were asymptomatic, that too many were entered into a non-randomized PCA registry because they were considered unsuitable for CEA, and that the unconventional primary end points were potentially misleading []. Asymptomatic carotid disease is the most common indication for CEA or PCA in the United States [], however, and not just for the convincing severity of stenosis (80-99%) that this trial required. In addition, participating surgeons may have been understandably reluctant to randomize certain patients who had multiple high-risk factors for CEA. Finally, although the inclusion of clinically unsuspected MIs was a novel approach to early outcome assessment, it is difficult to argue logically that these events should have been allowed to go undetected.

SPACE

The Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy (SPACE) trial is a non-inferiority study that was designed to demonstrate equivalence between PCA/stenting and CEA. In order to participate, interventionalists had to show proof of at least 25 successful consecutive PCA procedures. The virtues of the SPACE trial are its large size (1,200 symptomatic patients), which thusfar exceeds any similar RCT, and the fact that it has been supported predominantly by independent resources. Its perceived liabilities are that cerebral embolic protection was used during only 27% of the PCA procedures, and that recruitment was prematurely stopped for lack of funding after it was discovered that more than 2,500 patients would be necessary to confirm its interim results with adequate statistical power. At that time, the 30-day risk for death or ipsilateral stroke appeared comparable for PCA and CEA (6.8 and 6.3%, respectively), but the P-value for non-inferiority was only 0.9. No long-term event rates are available for the SPACE trial, but its trialists have stated that these outcomes will be published in the form of a meta-analysis in conjunction with other European RCTs [].

EVA-3S

The Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial is the most recent study summarized in Table 2 and could conceivably serve as a proxy for the evolution of PCA in other large population bases. Sponsored by the French Ministry of Health in 20 academic and 10 non-academic medical centers, this trial permitted the use of a variety of approved catheter devices. Carotid stenting was mandatory, but cerebral embolic protection (ultimately used in 92% of patients) was not routinely recommended until the 30-day stroke rate was discovered to be 3.9 (95% confidence interval, 0.9 to 16.7) times higher without embolic protection (27%, 4 out of 15) than with protection (8.6%, 5 out of 58) in the initial 73 patients treated by PCA []. Perhaps the most controversial element of this trial is that interventionalists who had no previous experience with PCA still were permitted to perform it in randomized patients under the supervision of tutors until they acquired the requisite number of 12 PCAs (or only five PCAs plus another 30 stenting procedures in aortic arch vessels) for full accreditation. Interventionalists also could begin using a new catheter device within the trial as soon as they had gained some familiarity with it in just two other cases.

Trial enrollment was stopped on the basis of safety and futility once the 30-day stroke or mortality rate in the first 527 treated patients was found to be so much higher for PCA (9.6 versus 3.9% for CEA; relative risk, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 5.1; P = 0.01) that more than 4,000 patients would have been necessary to demonstrate its non-inferiority to CEA. The EVA-3S trial has been criticized for the inexperience among its interventionalists and the lack of a standardized technique for PCA, but the flaws that some might find in this trial - the mix of community hospitals as well as referral centers, the mid-course changes to new or improved equipment, the low procedural volumes or on-the-job training by more experienced colleagues - are ubiquitous and may make its results more relevant to ‘real world’ practice []. The French trial was limited to symptomatic patients, but another national dataset also has shown that PCA/stenting was associated with higher risks for stroke or death than CEA in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in the United States during 2003 and 2004 [].

Ongoing trials

The International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS), or CAVATAS 2, and the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) are two major independent RCTs currently underway in Europe and North America, respectively. No outcome data are available from the ICSS, but the CREST has reported early results for a total of 749 patients who underwent PTA/stenting with routine embolic protection during a lead-in phase that was used to credential interventionalists. The 30-day stroke or mortality rate was significantly higher (12%, P < 0.0001) in octogenarians than it was in patients who were 70 to 79 (5.3%), 60 to 69 (1.3%) or less than 60 (1.7%) years of age []. Others have confirmed the unfavorable influence of advancing age on the risk of PCA in device regulatory trials [] and have attributed this to the arterial tortuosity and calcification that often occur in elderly patients, thus making catheter-directed devices more likely to provoke cerebral emboli [].

Implications for clinical practice

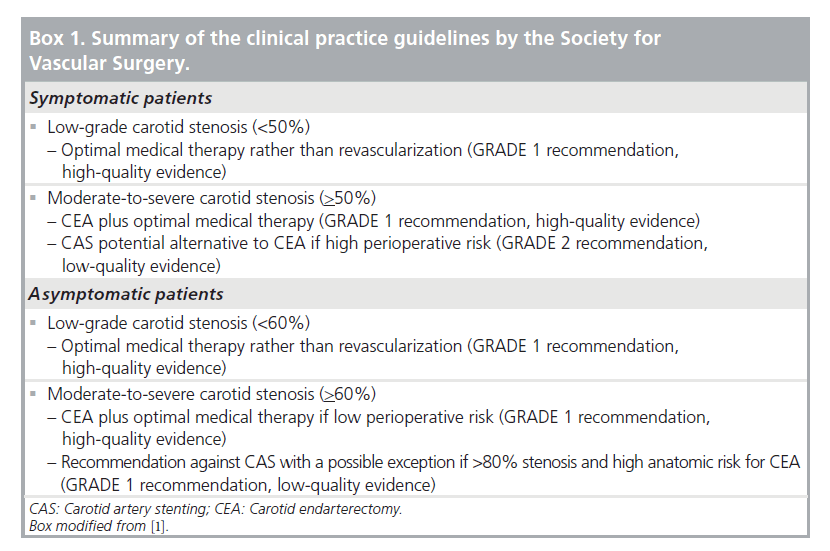

Citing much of the material covered in this review as well as additional sources in the literature, the Society for Vascular Surgery recently published clinical practice guidelines for the management of atherosclerotic carotid artery disease []. This document reconfirms the continued importance of the NASCET, ECST, ACAS and ACST in the selection of patients for either surgical or catheter-based intervention, emphasizing that patients who have symptomatic <50% stenosis or asymptomatic <60% stenosis are well suited to optimal medical management alone. These guidelines also propose that CEA plus medical therapy should remain the primary option for patients with more severe stenosis unless the ICSS and the CREST eventually prove otherwise. On the basis of current uncertainties, PCA generally seems most appropriate in the setting of these or similar trials until it has been shown conclusively to have the same safety and durability as CEA. In the meantime, exceptions favoring PCA can be justified for patients whose medical comorbidities or cervical anatomy make them questionable candidates for CEA.

Abbreviations

| ACAS | Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study |

| ACST | Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial |

| CAVATAS | Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study |

| CEA | carotid endarterectomy |

| CREST | Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent |

| ECST | European Carotid Surgery Trial |

| EVA-3S | Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis |

| ICSS | International Carotid Stenting Study |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| NASCET | North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial |

| NNT | number needed to treat |

| PCA | percutaneous carotid angioplasty |

| RCT | randomized clinical trial |

| SAPPHIRE | Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy |

| SPACE | Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy |

Notes

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://www.F1000.com/Reports/Medicine/content/1/18

Notes

Competing interests

The author was a participating surgeon in the SAPPHIRE trial but had no role in the design of the trial, the management or the interpretation of its data, or the preparation of its published reports.

References

Evaluated by Norman Hertzer 18 Apr 2008

Evaluated by Hans-Christoph Diener 6 Dec 2006

Evlauated by Norman Hertzer 27 Jul 2007

F1000 Factor 3.0 Recommended

Evaluated by Harri Jenkins 2 Jun 2008

PubMed • Full text • PDF

- 6Population

- 8Outcomes

Clinical Question

Acas Carotid Trial Hearing

In patients with asymptomatic significant carotid artery stenosis (≥60%), does immediate carotid endarterectomy (CEA) reduce the stroke risk as compared to deferral of CEA?

Bottom Line

In asymptomatic patients <75 years of age with asymptomatic significant carotid artery stenosis (≥60%), successful immediate CEA reduces 10-year risk of stroke without a significant increase in peri-operative mortality and morbidity as compared to deferred CEA.

Major Points

The stroke prevention after successful carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic stenosis (ACST-1) randomized 3,120 patients to assess the effect of immediate CEA on stroke risk as compared to deferred CEA.

In asymptomatic patients <75 years of age with asymptomatic significant carotid artery stenosis (≥60%), successful immediate CEA reduces 10-year risk of stroke without a significant increase in peri-operative mortality and morbidity as compared to deferred CEA.

Another study on asymptomatic patients with carotid stenosis is the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS).[1] In addition, the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial (CREST) trial enrolled both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.[2]

Guidelines

2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease[3]

- Selection of asymptomatic patients for carotid revascularization should be guided by an assessment of comorbid conditions, life expectancy, and other individual factors and should include a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure with an understanding of patient preferences. (Class I; Level of Evidence: C)

- It is reasonable to perform CEA in asymptomatic patients who have more than 70% stenosis of the internal carotid artery if the risk of perioperative stroke, MI, and death is low. (Class IIa; Level of Evidence: A)

- In symptomatic or asymptomatic patients at high risk of complications for carotid revascularization by either CEA or CAS because of comorbidities, the effectiveness of revascularization versus medical therapy alone is not well established. (Class IIb; Level of Evidence: B)

Design

- Multicenter, blinded, randomized, controlled trial

- N=3,120

- immediate CEA (n=1,560)

- deferral of any carotid procedure (n=1,560)

- Setting: 126 centers in 30 countries

- Enrollment: April 1993 to July 2003

- Median follow-up: 9 years

- Analysis: Intention-to-treat

- Primary outcome:

- peri-operative mortality and morbidity (death or stroke within 30 days)

- non-perioperative stroke

Population

Inclusion Criteria

- severe unilateral or bilateral carotid artery stenosis (no fixed cut-off but generally ≥60%)

- this stenosis had not caused stroke, transient cerebral ischemia, or any other relevant neurological symptoms in the past 6 months

- fit for surgery, if required

- no circumstance or condition precluded long-term follow-up

- doctor and patient were both substantially uncertain whether to choose immediate CEA or deferral of CEA.

Exclusion Criteria

These reasons are specified by the physician, not by the protocol

- a small likelihood of benefit:

- a carotid plaque not causing significant stenosis and confers a low risk of stroke

- patients with major life-threatening co-morbidities other than stroke

- poor CEA risk such as recent acute myocardial infarction and intra-cerebral tumors or aneurysm.

- re-stenosis following previous CEA

- emboli is likely to be from a cardiac source

Baseline Characteristics

This describes all randomized patients. There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the immediate and deferred CEA patients.

- Mean age (years): 68 (40-91)

- Male gender (%): 65.5

- Hypertension (%): 65

- Mean systolic blood pressure (mmHg): 153

- Diabetes (%): 20

- Mean cholesterol (mmol/L): 5.8

- Previous contralateral CEA (%): 24

Interventions

- Doppler ultrasound was used to assess carotid artery stenosis. Generally, the criteria was defined according to the NASCET trial.

- All patients received therapy targeting risk factors for stroke and death including smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia, polycythemia and ischemic heart disease

- Anti-platelet therapy was prescribed to majority of the patients unless there was a specific contraindication or the patient was already on anticoagulant therapy

Immediate CEA

- Procedure carried out as soon as possible using the surgeon's preferable technique

- 50% of patients underwent ipsilateral surgery by 1 month, 89.3% by 1 year after randomisation and 91·8% by 5 years after randomisation

- Shunting during surgery for maintaining cerebral perfusion was optional

- Antiplatelet therapy was generally prescribed for post-operative treatment

Deferral of CEA

- not to undergo CEA unless they develop symptoms suggestive of carotid artery ischemia or other definite indication for surgery was thought to have arisen

- 26% of patients in this group had CEA within 10 years

Outcomes

Comparisons are immediate CEA vs. deferred CEA

Primary Outcomes

- peri-operative mortality and morbidity (death or stroke within 30 days) at 5-years[4]

data expressed as % of total CEA

2.8% (2·0-3·9) vs. 4.5% (2·2-8·0) (P=NS)

overall the risk per CEA was 3·1% (95% CI 2·3-4·1)

peri-operative mortality and morbidity (death or stroke within 30 days) at 10-years

data expressed as % of total CEA

2.9% (2.1-3.8) vs. 3.6% (2.2-5.7) (P=NS)

overall the risk per CEA was 3·0% (95% CI 2·4-3.9)

non-perioperative stroke risk at 5-years

data expressed as events/person-years

4·1% vs. 10·0% (gain 5·9%; 95% CI 4·0-7·8; P<0.0001)

non-perioperative stroke risk at 10-years

data expressed as events/person-years

10·8% vs. 16·9% at (gain 6·1%; 95% CI 2·7-9·4; P=0.0004)

Secondary outcomes

Any stroke or perioperative death at 5 years

data expressed as events/CEA+other events

6·9% vs. 10·9% (gain 4·1%, 95% CI 2·0-6·2; P=0.0001)

Any stroke or perioperative death at 10 years

data expressed as events/CEA+other events

13·4% vs. 17·9% (gain 4·6%, 95% CI 1·2-7·9; P=0.009)

Subgroup Analysis

- At 10-years, the benefits of CEA was not significant for both men and for women ≥75 years old at entry to trial

- At 10-years, there was no significant heterogeneity between benefits in subgroups of gender, pre-randomisation cholesterol, pre-randomisation systolic blood pressure, severity of stenosis, diabetes mellitus, IHD, use of anti-hypertensive, anti-thrombotic or lipid-lowering agents at entry.

- At 10-years, there was no significant heterogeneity between perioperative hazards in subgroups of age, gender or severity of stenosis.

- However subgroup analyses are not definitive due to the small number of events in the trial.

Criticisms

- Uncertainty if patients achieved ideal blood pressure levels (<140/90 mm Hg) or LDL-C (<2·4 mmol/L) as recommended by JNC 7 and NCEP III guidelines. This affects their absolute risk for stroke.[5]

- Lipid-lowering therapy may have been suboptimal in the trial.[6]

- Ultrasound was used in the trial, which may be associated with its own imperfections as compared to modern imaging techniques, such as angiography.[7]

- Contemporary medical therapy has changed since the trial. Patients in the ACST did not receive best medical therapy as compared to modern practice.[8]

- Medical therapy was not standardized and left to the discretion of clinicians.[8]

- Surgeons in the trial were highly selected. It's important to consider if a comparable incidence of operative complications can be achieved in local centres.[7]

- It is unclear if females obtain as much benefit as males from CEA.[3][9]

Funding

UK Medical Research Council, BUPA Foundation, Stroke Association

Further Reading

- ↑Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995. 10;273(18):1421–8.

- ↑Brott TG, Hobson RW, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Treatment of Carotid-Artery Stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010. 1;363(1):11–23.

- ↑ 3.03.1Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, Bacharach JM, Barr JD, Bush RL, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery Developed in Collaboration With the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(8):e16–94.

- ↑Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502

- ↑Amarenco P, Labreuche J, Mazighi M. Lessons from carotid endarterectomy and stenting trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9746):1028-31

- ↑Paraskevas KI, Mikhailidis DP, Veith FJ. Best medical treatment for a symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):123; author reply 123-4

- ↑ 7.07.1Barnett HJ. Carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1122-3; author reply 1125-6.

- ↑ 8.08.1Jonas DE, Feltner C, Amick HR, Sheridan S, Zheng ZJ, Watford DJ, et al. Screening for Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 111. AHRQ Publication No. 13-05178-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014

- ↑Rothwell PM. ACST: which subgroups will benefit most from carotid endarterectomy? Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1122-3; author reply 1125-6